Comparing machine learning

algorithms for prediction of osteoporosis: A systematic review and

meta-analysis study

Esmat Mashoof1 , Khadijeh Moulaei2

, Khadijeh Moulaei2 , Naser Nasiri3*

, Naser Nasiri3*

1Department of Health

Information Technology, Varastegan Institute for Medical Sciences, Mashhad,

Iran

2Health Management

and Economics Research Center, Health Management Research Institute, Iran

University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3School of Public

Health, Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Kerman, Iran

|

Article Info

|

A B S T R A C T

|

|

Article type:

Review

|

Introduction:

Osteoporosis is a prevalent bone disease that affects millions of individuals

worldwide. Early identification and prediction of osteoporosis can enable

timely interventions and preventive measures. This study investigates the

potential of machine learning algorithms to accurately predict osteoporosis.

Material

and Methods: This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis

conducted by searching in three databases. Our search encompassed databases

such as Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus. Pertinent information from the

selected studies was independently extracted by two authors. The PRISMA

guidelines were followed to ensure a rigorous review process. The PROBAST tool

was utilized to assess the risk of bias in the included studies. Data

analysis was performed using Stata (v.17.1).

Results:

A total of 63 algorithms from 18 studies were evaluated. In terms of

predicting osteoporosis, support vector machine (SVM) and random forest (RF)

algorithms demonstrated the highest sensitivity. For SVM, the sensitivity and

diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) were 83.0% (95% confidence interval (CI):

76.0-88.0) and 10.4 (95% CI: 6.0-18.2), respectively. Similarly, in the case

of RF algorithm, the sensitivity and DOR were 81.0% (95% CI: 74.0-87.0) and

13.0 (95% CI: 7.7-21.2), respectively. The artificial neoural networks (ANN),

RF, and K-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithms exhibited the highest

specificity values: ANN- specificity of 79.0% (95% CI: 71.0-85.0) and DOR of

12.0 (7.3-18.7); RF- specificity of 75.0% (95% CI: 62.0-84.0) and DOR of 13.0

(7.7-21.2); KNN- specificity of 75.0% (95% CI: 67.0-82.0) and DOR of

7.7(6.6-9.0).

Conclusion:

Our study highlights the promising potential of machine learning algorithms

for the accurate prediction of osteoporosis. ANN model and SVM, RF, and KNN

algorithms have emerged as the most robust predictors. These findings

demonstrate substantial potential for aiding early detection and intervention

strategies against osteoporosis.

|

|

Article

History:

Received: 2026-01-10

Accepted: 2026-02-08

Published: 2026-02-10

|

|

* Corresponding

author:

Naser Nasiri

School of Public Health, Jiroft University of

Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Kerman, Iran

Email: nasiri.epi@gmail.com

|

|

Keywords:

Osteoporosis

Prediction

Machine Learning

Algorithm

|

|

Cite this paper as:

Mashoof S, Moulaei K, Nasiri

N. Comparing machine learning algorithms for

prediction of osteoporosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. Adv Med Inform. 2026; 2: 9.

|

Introduction

Osteoporosis, a common skeletal disorder, poses

significant challenges for individuals affected by it. This condition is

characterized by reduced bone density and deterioration of bone

microarchitecture, resulting in increased vulnerability to fractures [1]. Osteoporosis predominantly affects older adults,

particularly postmenopausal women [2], but can also occur

in men and younger individuals [3]. One of the primary

challenges of osteoporosis lies in its asymptomatic nature until a fracture

occurs, leading to delayed diagnosis and treatment initiation [4].

Moreover, the progressive nature of the disease increases the risk of recurrent

fractures and significant impairment in mobility and quality of life [5].

Osteoporosis presents numerous challenges for individuals

affected by the condition. One of the primary problems is the increased risk of

fractures, which can lead to pain, disability, and a significant decline in

quality of life [5, 6]. Osteoporotic

fractures, especially in the hip and spine, can result in prolonged

hospitalization, surgical interventions, and long-term rehabilitation [7]. Another issue is the asymptomatic nature of osteoporosis

until a fracture occurs, making it difficult to detect and intervene at an

early stage [8]. Additionally, the progressive nature of

the disease puts individuals at a higher risk of recurrent fractures [9], further exacerbating the physical and emotional burden [10]. Addressing these problems requires early detection and

prediction of osteoporosis.

The early detection and prediction of osteoporosis play a

crucial role in preventing debilitating fractures and implementing appropriate

interventions [11]. Traditional approaches for

osteoporosis prediction rely on risk assessment tools based on clinical factors

and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans. However, emerging research

suggests that machine learning techniques have the potential to improve the

accuracy and efficiency of osteoporosis prediction by integrating diverse data

sources [12]. These techniques can integrate various types

of data, such as clinical, genetic, and imaging information, to improve the

accuracy and efficiency of predicting osteoporosis risk.

Machine learning models have the potential to identify

high-risk individuals earlier, enabling timely interventions and preventive

measures to mitigate the progression of osteoporosis and reduce fracture risk [13, 14]. In this context, we present a

systematic review and meta-analysis study aimed at evaluating the predictive

capabilities of machine learning models in identifying individuals at risk of

osteoporosis. Through synthesizing and analyzing existing literature, we aim to

provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of research in this field

and shed light on the potential clinical implications of machine learning-based

osteoporosis prediction.

Material and Methods

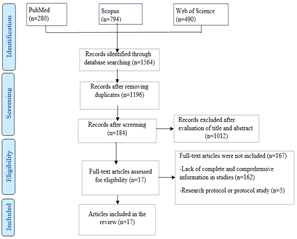

In this study, we utilized the Preferred Reporting

Information for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) checklist to

select studies and report the results.

Data Sources and Search strategy

To conduct this study, we conducted searches in Web of

Science, PubMed, and Scopus databases to identify relevant published papers

until July 10, 2023. To retrieve the relevant study, we employed the following

search strategy:

((“Machine learning” OR “artificial intelligence” OR

“machine learning algorithms” OR “deep learning” OR “neural networks” OR

“artificial neural network”) AND (“low bone density” OR “osteoporosis” OR

“osteopenia”))

Eligibility criteria

This study included articles that specifically addressed

the prediction of osteoporosis using machine learning techniques. The inclusion

criteria considered articles published in English, centering on the use of

machine learning for osteoporosis prediction, and reporting machine learning

algorithms, sensitivity, specificity, and/or receiver operating characteristic

curve (ROC). Exclusion criteria were applied to papers that did not primarily

concentrate on the prediction of osteoporosis with machine learning.

Additionally, letters to the editor, conference abstracts, book chapters, and books,

were excluded from the study.

Study selection

Initially, abstracts of relevant articles were collected

from three databases: Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus. These study abstracts

were then imported into EndNote 21. Afterward, any duplicate articles were

removed. Two researchers reviewed the titles and abstracts to select the

relevant articles based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

In instances of disagreement, the research team members

resolved disagreements through discussions, arriving at the ultimate decision

for each article. Ultimately, the full text of the articles was examined to extract

essential data.

Data charting process and data items

For each study, the following information was extracted:

authors name, year of publication, study aim, used database, machine learning

algorithms used, sample size, as well as measures used for assessing algorithm

performance such as specificity, sensitivity, accuracy, positive predictive

value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curve. For case studies lacking details on positive and

negative cases, we conducted manual calculations using recognized formulas based

on statistics available in the manuscripts or provided by the authors. When required

data were not presented in the manuscripts or abstracts, we contacted the

authors for clarification. Our initial contact prioritized the corresponding

author, followed by the first author, and then the last author. If attempts to

contact the authors in this specified sequence were unsuccessful, the studies

were excluded from the meta-analysis. Furthermore, manuscripts or abstracts

without sufficient evaluation data after author contact were also excluded.

Critical appraisal of individual sources of studies

To critically appraise individual sources of studies, we

utilized the prediction model risk of bias assessment tool (PROBAST). This tool

facilitates the assessment of both the risk of bias (ROB) and the applicability

of diagnostic and prognostic prediction model studies. The PROBAST tool

consists of 20 signaling questions that are categorized into four domains: participants,

predictors, outcome, and analysis. This accompanying document provides a

comprehensive explanation and elaboration for each domain and signaling

question's inclusion. It serves as a helpful resource for researchers,

reviewers, readers, and guideline developers, aiding them in effectively

employing the tool to evaluate both the risk of bias and applicability concerns

within their assessments [15].

Statistical analysis

In this study, a meta-analysis was conducted using a 2x2

contingency table. The table was constructed to include values for true false

positive (FP), positive (TP), false negative (FN), and true negative (TN).

Meta-analysis for diagnostic tests was carried out when more than four studies

reported algorithms for predicting osteoporosis. The models encompassed

estimates of sensitivity, specificity, diagnostic odds ratio, positive

likelihood, negative likelihood, and ROC. The 'metandi' and 'metadta' commands

in Stata (versions 17.1 and 14.1) were used to model these values along with

95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

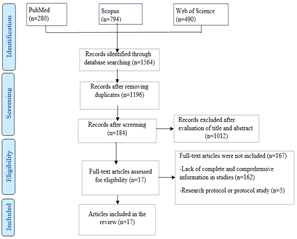

After extracting 1564 papers from three databases,

duplicate entries were excluded, resulting in a collection of 1196 unique

studies. Subsequently, these studies underwent a meticulous review and

evaluation based on pre-established criteria for inclusion and exclusion. After

this comprehensive assessment, a final set of 17 articles was selected for

inclusion in the research (Fig 1).

Fig 1: PRISMA diagram depicting the screening

and inclusion process of studies

Characteristics of the included studies

Table 1 provides a thorough summary of the selected

studies. A total of 63 algorithms from 17 distinct studies were evaluated. The

majority of the studies were conducted in China (n=6) and Korea (n=5).

Table 1: Comprehensive examination of the

chosen studies

|

Ref

|

Year

|

Country

|

Database name

|

Number of samples

|

Number of algorithms

|

Algorithm name

|

|

[16]

|

2009

|

Korea

|

Korea National Health and

Nutrition Examination Surveys (KNHANES)

|

1792

|

7

|

KNN, random forest (RF), gradient

boosting machine (GBM), SVM, ANN, decision tree (DT), and logistic regression

(LR)

|

|

[17]

|

2010

|

Chaina

|

Medical records of participants

at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University and the

Affiliated Hospital of the Medical School of Ningbo University.

|

1559

|

1

|

ANN

|

|

[18]

|

2013

|

Taiwan

|

The dataset in this study, which

included SNPs, age, menopause, and BMI, was the same dataset used in a

previous study by the first author of this paper [9]

|

295

|

3

|

Multilayer feedforward neural

network (MFNN), Naive Bayes (NB), and LR

|

|

[19]

|

2013

|

Korea

|

Korea National Health and

Nutrition Examination Surveys (KNHANES)

|

1674

|

4

|

SVM, RF, ANN, and LR

|

|

[20]

|

2013

|

Korea

|

Korea National Health and

Nutrition Examination Surveys (KNHANES V-1)

|

1674

|

4

|

SVM, RF, ANN, and LR

|

|

[21]

|

2016

|

China

|

Data collated from chain

hospitals

|

119

|

2

|

ANN, LR

|

|

[22]

|

2019

|

Chaina

|

Data were collated from the

electronic medical record systems of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin

Medical University and the Affiliated Hospital of the Medical School of

Ningbo University.

|

1559

|

1

|

ANN

|

|

[14]

|

2020

|

Korea

|

Korea National Health and

Nutrition Examination Surveys (KNHANES)

|

1792

|

7

|

LR, KNN, DT, RF, GBM, SVM, ANN

|

|

[23]

|

2021

|

Taiwan

|

Data were collected from

individuals living in the community who took part in health checkup programs

at a medical center in northern Taiwan from 2008 to 2018.

|

5982

|

5

|

ANN, SVM, RF, KNN, LR

|

|

[24]

|

2021

|

China

|

Data collection from Hospital of

Chongqing Medical University

|

1419

|

4

|

Deep Belief Network (DBN), SVM

ANN, and combinatorial heuristic method (Genetic Algorithm - Decision Tree

(GA-DT))

|

|

[25]

|

2021

|

Korea

|

Data collated from Hallym

University Sacred hospital

|

500

|

1

|

RF

|

|

[26]

|

2021

|

Greece

|

Data was collated from cases

referred to a university hospital's specialized bone marrow imaging referral

clinic.

|

213

|

3

|

Extreme gradient boosting

(XGBoost), CatBoost and SVM

|

|

[27]

|

2022

|

India

|

Data collated from Abhilasha

orthopedic hospital in Banashankari

|

80

|

4

|

DT, NB, SVM, KNN

|

|

[28]

|

2022

|

China

|

Data collated from the Second

Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University

|

172

|

5

|

Gaussian naïve Bayes (GNB), RF,

LR, SVM, Gradient boosting machine (GBM), and XGBoost

|

|

[29]

|

2023

|

USA

|

Data for this secondary analysis

was collected from patients participating in the Study of Women's Health

Across the Nation (SWAN), who initially joined between 1996 and 1997 at seven

designated research centers across the USA.

|

1,685

|

1

|

LR

|

|

[30]

|

2023

|

China

|

Data collated from department of

Endocrinology at Cangzhou Central Hospital

|

433

|

9

|

XGBoost, LR, Light Gradient

Boosting Machine (LightGBM), RF, Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), Gaussian Naive

Bayes (Gaussian NB), Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost), SVM, and KNN

|

|

[31]

|

2023

|

USA

|

Data collected from a tertiary

care academic centre.

|

273

|

2

|

SVM, and RF

|

Machine learning algorithms and osteoporosis prediction

We present the results of six algorithms used for

predicting osteoporosis: ANN, was recommended in 10 studies, encompassing a

sample size of 17,570; LR was recommended in 11 studies, with a total sample

size of 15,618; SVMs were recommended in 12 studies, involving a sample size of

15,504; RF algorithms were recommended in 9 studies, with a sample size of

12,618; KNN algorithms were recommended in six studies, with a sample size of

10,079; and DT algorithms were recommended in four studies, with a sample size

of 5,083.

The results of this review reveal that SVM and RF

algorithms exhibited the highest sensitivity, whereas the ANN model, RF, and

KNN algorithms demonstrated the highest levels of specificity. Subsequently,

detailed findings for each algorithm are described below.

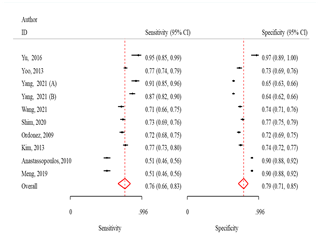

ANN

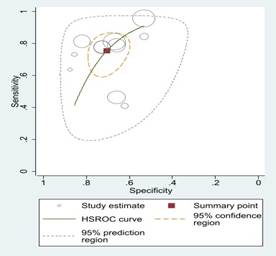

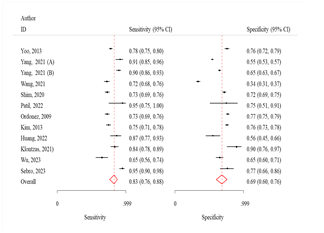

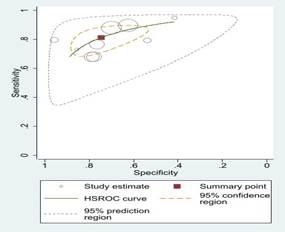

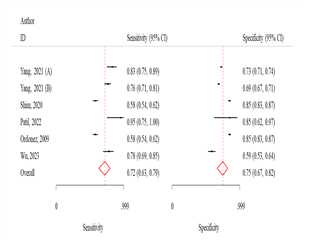

The sensitivity and specificity were 76.0% (95% CI:

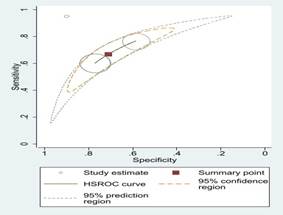

66.0-83.0) and 79.0% (95% CI: 71.0-85.0), respectively (Fig 2). The odds of

obtaining positive results in the test outcomes for osteoporosis patients were

12.0 times higher (95% CI: 7.3-18.7) than in non-patients, and the likelihood

of a positive test result was 3.6 times higher (95% CI: 2.7-4.8) (Table 2)

LR algorithm

The sensitivity and specificity were 76.0 (95% CI:

65.0-84.0) and 70.0 (95% CI: 63.0-77.0) respectively (Fig 2). The odds of

obtaining positive results in the test outcomes for osteoporosis patients was

7.4 times (95% CI: 4.3-12.5) higher than in non-patients, also probable

positivity in the test results was 2.6 times (95% CI: 2.0-3.2) (Table 2).

SVM algorithm

The sensitivity and specificity were 83.0% (95% CI:

76.0-88.0) and 69.0% (95% CI: 60.0-76.0), respectively (Fig 2). The odds of

obtaining positive results in the test outcomes for osteoporosis patients were

10.4 times higher (95% CI: 6.0-18.2) than in non-patients, and the likelihood

of a positive test result was 2.6 times higher (95% CI: 2.0-3.4) (Table 2).

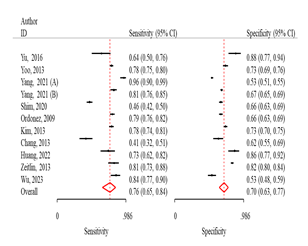

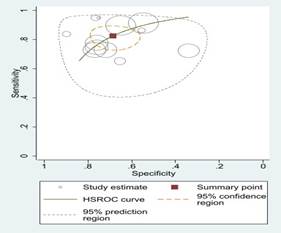

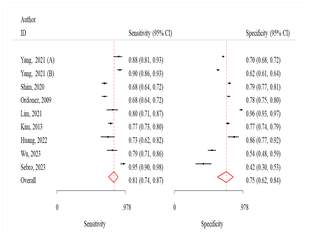

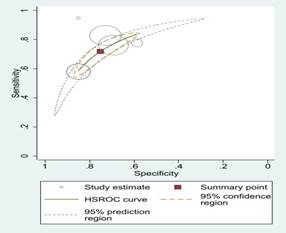

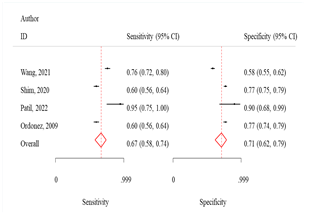

RF algorithm

The sensitivity and specificity were 81.0 (95% CI:

74.0-87.0) and 75.0 (95% CI: 62.0-84.0) respectively (Fig 3). The odds of

obtaining positive results in the test outcomes for osteoporosis patients was

13.0 times (95% CI: 7.7-21.2) higher than in non-patients, also probable

positivity in the test results was 3.2 times (95% CI: 2.1-4.8) (Table 2).

KNN algorithm

The sensitivity and specificity were 72.0% (95% CI:

63.0-70.0) and 75.0% (95% CI: 67.0-82.0), respectively (Fig 3). The odds of

obtaining positive results in the test outcomes for osteoporosis patients were

7.7 times higher (95% CI: 6.6-9.0) than in non-patients. Additionally, the

likelihood of a positive test result was 2.8 times higher (95% CI: 2.3-3.5)

(Table 2).

DT algorithm

The sensitivity and specificity were 67.0% (95% CI:

58.0-74.0) and 71.0% (95% CI: 62.0-79.0), respectively (Fig 3). The odds of

obtaining positive results in the test outcomes for osteoporosis patients were

5.0 times higher (95% CI: 4.3-5.6) than in non-patients. Additionally, the

likelihood of a positive test result was 2.3 times higher (95% CI: 2.0-2.7)

(Table 2).

Table 2: Algorithms

employed in the prediction of osteoporosis

|

Algorithms

|

Algorithm’s frequency in studies

|

Sensitivity (95%CI)

|

Specificity (95%CI)

|

DOR

|

Positive likelihood ratio

|

Negative likelihood ratio

|

I2

|

|

ANN

|

10

|

76.0

(66.0-83.0)

|

79.0

(71.0-85.0)

|

12.0

(7.3-18.7)

|

3.6 (2.7-4.8)

|

3.3 (2.4-4.5)

|

95.0

|

|

LR

|

11

|

76.0

(65.0-84.0)

|

70.0

(63.0-77.0)

|

7.4

(4.3-12.5)

|

2.6 (2.0-3.2)

|

2.9 (2.0-4.2)

|

93.3

|

|

SVM

|

12

|

83.0

(76.0-88.0)

|

69.0

(60.0-76.0)

|

10.4

(6.0-18.2)

|

2.6 (2.0-3.4)

|

4.0 (2.8-5.6)

|

87.5

|

|

RF

|

9

|

81.0

(74.0-87.0)

|

75.0

(62.0-84.0)

|

13.0

(7.7-21.2)

|

3.2 (2.1-4.8)

|

4.0 (2.9-5.4)

|

93.2

|

|

KNN

|

6

|

72.0

(63.0-70.0)

|

75.0

(67.0-82.0)

|

7.7

(6.6-9.0)

|

2.8 (2.3-3.5)

|

2.7 (2.2-3.3)

|

0.67

|

|

DT

|

4

|

67.0

(58.0-74.0)

|

71.0

(62.0-79.0)

|

5.0

(4.3-5.6)

|

2.3 (2.0-2.7)

|

2.1 (2.0-2.5)

|

0.2

|

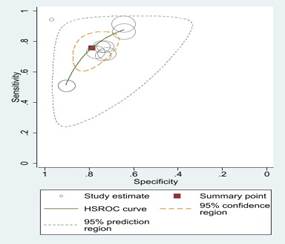

Fig 2: Sensitivity

and specificity and ROC curves comparing different machine learning algorithms

Fig 3: Comparison

of various machine learning algorithms using Sensitivity and Specificity along

with ROC curves.

Discussion

To our current understanding, this study is the inaugural

instance of a meta-analytic methodology employed in the field of machine

learning research, encompassing numerous studies with thousands of

participants, and centering on predicting machine learning algorithms'

performance in osteoporosis. This study stands out as a groundbreaking endeavor

in the realm of meta-analytic approaches applied to machine learning research. Thorough

examination encompasses numerous studies with thousands of participants, providing

insights into the effectiveness of different machine learning algorithms for

predicting osteoporosis. The findings from this review indicate that SVM and RF

algorithms exhibited the highest sensitivity. On the other hand, the ANN model,

RF, and KNN algorithms demonstrated the highest specificity values.

As it mentioned a significant finding of this study is

the elevated performance of the SVM and RF algorithms in terms of sensitivity.

Various studies [32, 33] have shown

that SVM and RF algorithms are very effective in predicting osteoporosis. This

observation resonates with previous research demonstrating the prowess of these

algorithms in capturing intricate patterns within datasets [34].

The capacity of SVM and RF algorithms to detect even subtle variations within

data suggests their suitability for identifying individuals at risk of

osteoporosis at an early stage [32]. This aspect of the

findings underscores the importance of these algorithms as potential tools in

clinical settings, enabling healthcare practitioners to intervene promptly and

implement preventive measures to mitigate the progression of osteoporosis.

The elevated sensitivity observed in these algorithms

could be attributed to their underlying mechanisms. SVM works by finding the

optimal hyperplane that maximally separates different classes in the dataset.

This capability enables SVM to accurately discriminate between healthy

individuals and those at risk of osteoporosis, even when the differences are

subtle [35]. On the other hand, RF employs an ensemble of

decision trees to make predictions [36]. By combining the

outputs of multiple trees, RF can capture complex interactions among variables

and make robust predictions, which proves beneficial in identifying early signs

of osteoporosis. As it mentioned a significant finding of this study is the elevated

performance of the SVM and RF algorithms in terms of sensitivity. This

observation resonates with previous research demonstrating the prowess of these

algorithms in capturing intricate patterns within datasets.

This aspect of the findings underscores the importance of

these algorithms as potential tools in clinical settings. The ability of SVM

and RF algorithms to identify individuals at risk with high sensitivity

suggests their potential application in real-world clinical settings. Javaid et

al. [37], mentioned that healthcare practitioners can

leverage these algorithms to accurately identify those who need closer

monitoring or preventive measures. This proactive approach could lead to

improved patient outcomes, reduced healthcare costs, and an overall enhancement

in the management of osteoporosis.

Conversely, the study also brings attention to the high

specificity values demonstrated by the ANN model, RF, and KNN algorithms. This

facet of the findings emphasizes the accuracy of these algorithms in correctly

identifying individuals without osteoporosis, further establishing their

utility in the clinical context. The ability of these algorithms to minimize

false positives can significantly contribute to reducing unnecessary

interventions or treatments for individuals who are not at risk, thereby optimizing

medical resources and patient care strategies. The success of these algorithms

in achieving high specificity can be attributed to their unique characteristics

and underlying mechanisms. Yu et al. [21], pointed out

that ANNs are adept at learning complex patterns and relationships within data

through interconnected layers of neurons. This ability enables them to identify

subtle patterns that may indicate the absence of osteoporosis, leading to

accurate predictions of negative cases.

Similarly, RF harnesses the power of ensemble learning by

combining multiple decision trees, which collectively make robust predictions [38]. This ensemble approach enhances RF's ability to

correctly classify negative cases by mitigating the impact of noisy data or

outlier influences. KNN relies on proximity-based classification, identifying

the class of a data point based on the classes of its neighboring data points [39]. This local decision-making process contributes to KNN's

high specificity, as it can effectively discriminate between different classes

within the dataset.

Furthermore, the article's emphasis on sample studies,

such as Shim et al. [39], and Thawnashom et al. [40], underlines the consistency of the findings across

different datasets. This not only adds credibility to the results but also

indicates the generalizability of ANN, RF, and KNN algorithms' high specificity

in diverse scenarios, reinforcing their potential as valuable tools in clinical

applications. In clinical practice, high specificity holds immense value.

Accurately identifying individuals without osteoporosis reduces unnecessary

stress, interventions, and treatments for those who do not require them. This

is particularly relevant in the context of osteoporosis, where overdiagnosis

and overtreatment can have negative consequences. The precision offered by ANN,

RF, and KNN algorithms can contribute to more targeted and efficient healthcare

strategies, ultimately leading to improved patient experiences and outcomes.

In essence, this study offers a comprehensive overview of

the predictive capacities of various machine learning algorithms in the domain

of osteoporosis. The identification of algorithms that excel in sensitivity and

specificity aspects underscores their potential for aiding clinicians in making

informed decisions and improving patient outcomes. As the first of its kind to

undertake a meta-analysis on this subject, this study not only expands our

understanding of the intersection of machine learning and osteoporosis but also

sets a precedent for future research endeavors seeking to harness the power of

data-driven approaches in medical prediction and diagnosis.

Study limitation

This review was subject to two limitations. Firstly, it

exclusively incorporated studies that had been published in the English

language, thus disregarding any research available in other languages. For a

more encompassing perspective, forthcoming studies should contemplate the

incorporation of articles published in languages other than English. Secondly,

the quest for pertinent studies was restricted to just three scientific

databases: Scopus, PubMed, and Web of Science. To achieve more thorough outcomes,

upcoming research should broaden their search scope to encompass a wider array

of databases.

Conclusion

In summary, our comprehensive review and meta-analysis

shed light on the remarkable potential of machine learning algorithms in

predicting osteoporosis. Specifically, ANN and SVM, RF, and KNN algorithms have

notably emerged as preeminent predictors, showcasing their robustness. The

amalgamation of diverse studies presents a compelling case for the efficacy of

these algorithms in proficiently recognizing individuals at risk of

osteoporosis.

This significant advancement not only offers the

potential for early interventions and enhanced results for patients but also

marks the beginning of a new era characterized by personalized and targeted

approaches for managing this incapacitating condition. Utilizing the potential

of machine learning, healthcare professionals have the opportunity to transform

the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis, leading to a fundamental change

that may ease the impact of the disease and provide a more optimistic outlook

for those facing it. The results of this meta-analysis establish a solid

groundwork for future research, emphasizing the importance of incorporating

machine learning methods into regular clinical procedures. This integration has

the potential to equip healthcare providers worldwide with powerful tools to

efficiently address osteoporosis.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the

Central Library and Documentation Center of Kerman University of Medical

Sciences for providing access to the knowledge base references required for

this study.

Author’s contribution

KM and NN: Conceived the study design; KM, EM, and NN: Conducted

title/abstract and full-text screening; KM and NN: Performed the data

extraction; KM and NN: wrote the manuscript.

All authors contributed to the drafting the manuscript,

read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding

the publication of this study.

Ethical Approval

Not Applicable.

Financial disclosure

No financial interests related to the material of this

manuscript have been declared.

References

1.

Mirza F, Canalis E. Management of endocrine

disease: Secondary osteoporosis: Pathophysiology and management. Eur J

Endocrinol. 2015; 173(3): R131-51. PMID: 25971649 DOI: 10.1530/EJE-15-0118

[PubMed]

2.

Gulsahi A. Osteoporosis and jawbones in women. J

Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2015; 5(4): 263-7. PMID: 26312225 DOI: 10.4103/2231-0762.161753

[PubMed]

3.

Cole ZA, Dennison EM, Cooper C. Osteoporosis

epidemiology update. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008; 10(2): 92-6. PMID: 18460262 DOI: 10.1007/s11926-008-0017-6 [PubMed]

4.

Sinaki M. Critical appraisal of physical

rehabilitation measures after osteoporotic vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int.

2003; 14(9): 773-9. PMID: 12904834 DOI: 10.1007/s00198-003-1446-8

[PubMed]

5.

Miyakoshi N, Itoi E, Kobayashi M, Kodama H. Impact

of postural deformities and spinal mobility on quality of life in

postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2003; 14(12): 1007-12. PMID: 14557854 DOI: 10.1007/s00198-003-1510-4 [PubMed]

6.

Sozen T, Ozısık L, Basaran NC. An

overview and management of osteoporosis. Eur J Rheumatol. 2017; 4(1): 46-56. PMID: 28293453 DOI: 10.5152/eurjrheum.2016.048 [PubMed]

7.

Lippuner K, Rimmer G, Stuck AK, Schwab P, Bock

O. Hospitalizations for major osteoporotic fractures in Switzerland: A

long-term trend analysis between 1998 and 2018. Osteoporos Int. 2022; 33(11): 2327-35.

PMID: 35916908 DOI: 10.1007/s00198-022-06481-0 [PubMed]

8.

Sukegawa S, Fujimura A, Taguchi A, Yamamoto N, Kitamura

A, Goto R, et al. Identification of osteoporosis using ensemble deep

learning model with panoramic radiographs and clinical covariates. Sci Rep.

2022; 12(1): 6088. PMID: 35413983 DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-10150-x

[PubMed]

9.

Ponnusamy KE, Iyer S, Gupta G, Khanna A. Instrumentation

of the osteoporotic spine: Biomechanical and clinical considerations. Spine J.

2011; 11(1): 54-63. PMID: 21168099 DOI: 10.1016/j.spinee.2010.09.024

[PubMed]

10.

Dempster DW. Osteoporosis and the burden of

osteoporosis-related fractures. Am J Manag Care. 2011; 17(Suppl 6): S164-9.

PMID: 21761955 [PubMed]

11.

Tejaswini E, Vaishnavi P, Sunitha R. Detection and

prediction of osteoporosis using impulse response technique and artificial

neural network. International Conference on Advances in Computing,

Communications and Informatics. IEEE; 2016.

12.

Anam M, Ponnusamy V, Hussain M, Nadeem MW, Javed M,

Goh HG, et al. Osteoporosis prediction for trabecular bone using machine

learning: A review. Computers, Materials and Continua.

2020; 67(1): 89-105.

13.

De Vries BCS, Hegeman JH, Nijmeijer W, Geerdink J, Seifert

C, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM. Comparing three machine learning approaches to

design a risk assessment tool for future fractures: Predicting a subsequent

major osteoporotic fracture in fracture patients with osteopenia and

osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2021; 32(3): 437-49. PMID: 33415373 DOI: 10.1007/s00198-020-05735-z

[PubMed]

14.

Shim J-G, Kim DW, Ryu K-H, Cho EA, Ahn JH, Kim

JI, et al. Application of machine learning approaches for osteoporosis risk

prediction in postmenopausal women. Arch Osteoporos. 2020; 15(1): 169. PMID: 33097976 DOI: 10.1007/s11657-020-00802-8 [PubMed]

15.

Moons KGM, Wolff RF, Riley RD, Whiting PF, Westwood

M, Collins GS, et al. PROBAST: A tool to assess the risk of bias and

applicability of prediction model studies. Ann Intern Med. 2019; 170(1): W1-33.

PMID: 30596876 DOI: 10.7326/M18-1377 [PubMed]

16.

Ordonez C, Matias JM, Juez JFD, Garcia PJ. Machine

learning techniques applied to the determination of osteoporosis incidence in

post-menopausal women. Mathematical and Computer Modelling. 2009; 50: 673-9.

17.

Anastassopoulos G, Adamopoulos A, Galiatsatos D, Drosos

G. Osteoporosis risk factor estimation using artificial neural networks and

genetic algorithms. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013: 190: 186-8. PMID:

23823417 [PubMed]

18.

Chang HW, Chiu YH, Kao HY, Yang CH, Ho WH. Comparison

of classification algorithms with wrapper-based feature selection for

predicting osteoporosis outcome based on genetic factors in a Taiwanese women

population. Int J Endocrinol. 2013; 2013: 850735. PMID: 23401685 DOI: 10.1155/2013/850735

[PubMed]

19.

Kim SK, Yoo TK, Oh E, Kim DW. Osteoporosis risk

prediction using machine learning and conventional methods. Annu Int Conf IEEE

Eng Med Biol Soc. 2013; 2013: 188-91. PMID: 24109656 DOI: 10.1109/EMBC.2013.6609469

[PubMed]

20.

Yoo TK, Kim SK, Kim DW, Choi JY, Lee WH, Oh

E, et al. Osteoporosis risk prediction for bone mineral density assessment of

postmenopausal women using machine learning. Yonsei Med J. 2013; 54(6): 1321-30.

PMID: 24142634 DOI: 10.3349/ymj.2013.54.6.1321 [PubMed]

21.

Yu XH, Ye C, Xiang L. Application of artificial

neural network in the diagnostic system of osteoporosis. Neurocomputing. 2016;

214: 376-81.

22.

Meng J, Sun N, Chen YL, Li Z, Cui X, Fan

J, et al. Artificial neural network optimizes self-examination of osteoporosis

risk in women. J Int Med Res. 2019; 47(7): 3088-98. PMID: 31179797 DOI: 10.1177/0300060519850648

[PubMed]

23.

Yang WYO, Lai CC, Tsou MT, Hwang LC. Development of

machine learning models for prediction of osteoporosis from clinical health examination

data. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(14): 7635. PMID: 34300086 DOI: 10.3390/ijerph18147635 [PubMed]

24.

Wang YQ, Wang LX, Sun YL, Wu M, Ma Y, Yang

L, et al. Prediction model for the risk of osteoporosis incorporating factors

of disease history and living habits in physical examination of population in

Chongqing, Southwest China: Based on artificial neural network. BMC Public

Health. 2021; 21(1): 991. PMID: 34039329 DOI: 10.1186/s12889-021-11002-5

[PubMed]

25.

Lim HK, Ha HI, Park SY, Han J. Prediction of

femoral osteoporosis using machine-learning analysis with radiomics features

and abdomen-pelvic CT: A retrospective single center preliminary study. PLoS

One. 2021; 16(3): e0247330. PMID: 33661911 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247330

[PubMed]

26.

Klontzas ME, Manikis GC, Nikiforaki K, Vassalou EE, Spanakis

K, Stathis I, et al. Radiomics and machine learning can differentiate transient

osteoporosis from avascular necrosis of the hip. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021; 11(9):

1686. PMID: 34574027 DOI: 10.3390/diagnostics11091686 [PubMed]

27.

Patil KA, Prashanth KVM, Ramalingaiah A.

Classification of osteoporosis in the lumbar vertebrae using L2 regularized neural

network based on PHOG features. International Journal of Advanced Computer

Science and Applications. 2022; 13(4): 413-23.

28.

Huang CB, Hu JS, Tan K, Zhang W, Xu TH, Yang

L. Application of machine learning model to predict osteoporosis based on

abdominal computed tomography images of the psoas muscle: A retrospective

study. BMC Geriatr. 2022; 22(1): 796. PMID: 36229793 DOI: 10.1186/s12877-022-03502-9

[PubMed]

29.

Zeitlin J, Parides MK, Lane JM, Russell LA, Kunze

KN. A clinical prediction model for 10-year risk of self-reported osteoporosis

diagnosis in pre- and perimenopausal women. Arch Osteoporos. 2023; 18(1): 78. PMID: 37273115 DOI: 10.1007/s11657-023-01292-0 [PubMed]

30.

Wu X, Zhai F, Chang A, Wei J, Guo Y, Zhang

J. Application of machine learning algorithms to predict osteoporosis in

postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Endocrinol Invest. 2023; 46(12):

2535-46. PMID: 37171784 DOI: 10.1007/s40618-023-02109-0

[PubMed]

31.

Sebro R, Elmahdy M. Machine learning for opportunistic

screening for osteoporosis and osteopenia using knee CT scans. Can Assoc Radiol

J. 2023; 74(4): 676-87. PMID: 36960893 DOI: 10.1177/08465371231164743

[PubMed]

32.

Lin Y-T, Chu C-Y, Hung K-S, Lu C-H, Bednarczyk

EM, Chen H-Y. Can machine learning predict pharmacotherapy outcomes? An

application study in osteoporosis. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2022; 225: 107028.

PMID: 35930862 DOI: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2022.107028 [PubMed]

33.

Fasihi L, Tartibian B, Eslami R, Fasihi H.

Artificial intelligence used to diagnose osteoporosis from risk factors in

clinical data and proposing sports protocols. Sci Rep. 2022; 12(1): 18330. PMID: 36316387 DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-23184-y [PubMed]

34.

Maroco J, Silva D, Rodrigues A, Guerreiro M, Santana

I, de Mendonca A. Data mining methods in the prediction of Dementia: A

real-data comparison of the accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of linear

discriminant analysis, logistic regression, neural networks, support vector

machines, classification trees and random forests. BMC Res Notes. 2011; 4: 299.

PMID: 21849043 DOI: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-299 [PubMed]

35.

Yao Y, Liu Y, Yu Y, Xu H, Lv W, Li Z, et al. K-SVM:

An effective SVM algorithm based on K-means clustering. Journal of Computers.

2013; 8(10): 2632-9.

36.

Qiu X, Zhang L, Suganthan PN, Amaratunga GAJ.

Oblique random forest ensemble via least square estimation for time series

forecasting. Information Sciences. 2017; 420:

249-62.

37.

Javaid M, Haleem A, Singh RP, Suman R, Rab S. Significance

of machine learning in healthcare: Features, pillars and applications. International Journal of Intelligent Networks. 2022;

3: 58-73.

38.

Belgiu M, Dragut L. Random forest in remote

sensing: A review of applications and future directions. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. 2016;

114: 24-31.

39.

Saputra M, Mawengkang H, Nababan E. Gini index with

local mean based for determining k value in k-nearest neighbor classification.

Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2019; 1235: 012006.

40.

Thawnashom K, Pornsawad P, Makond B. Machine

learning's performance in classifying postmenopausal osteoporosis Thai

patients. Intelligence-Based Medicine. 2023; 7:

100099.