Usability evaluation of the Doctor Saina online consultation

application using the think-aloud method

Faezeh Raje1, Fateme

Moghbeli2 , Zahra Sangsefidi1

, Zahra Sangsefidi1 , Hamed Maktabdar Roshkhar3,

Mohammad Reza Mazaheri Habibi1*

, Hamed Maktabdar Roshkhar3,

Mohammad Reza Mazaheri Habibi1*

1Department of Health Information Technology, Varastegan Institute for Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

2Statistical Data

Analyst- Researcher and Assessment Services, York Region District Board (YRDSB),

Ontario, Canada

3Sadjad University of

Technology, Mashhad, Iran

|

Article Info

|

A B S T R A C T

|

|

Article type:

Research

|

Introduction:

The rapid advancement of technology and economic growth has created both

opportunities and challenges in healthcare accessibility. The unequal

distribution of medical resources, which disproportionately favors

economically developed regions, has led to a decline in the quality and

efficiency of healthcare services in rural and underdeveloped areas,

highlighting the urgent need for innovative solutions. Telemedicine

effectively overcoming geographical barriers and improving access to medical

care. However, usability issues in some of these applications present

significant challenges, potentially compromising service quality and user

experience. This study aimed to evaluate the usability of the Doctor Saina

application, identifying key factors that influence its effectiveness, user

satisfaction, and overall success.

Material

and Methods: In this study, digital health application Doctor Saina

which facilitate online medical consultations, making healthcare services

more accessible, was examined. A laboratory-based usability evaluation was

conducted using a predefined scenario-driven approach and the think-aloud

method with 15 participants. The identified usability issues were categorized

using the Van den Haak classification framework, and their severity was

assessed based on Nielsen’s heuristic evaluation model.

Results:

The average duration of the usability evaluation per

participant was 22.08 minutes. During the evaluation process, 23 issues were

identified by the users, 5 of which had a severity greater than 2. The most

frequent usability issues identified by users were in the Comprehensiveness

category (43.5%). During the evaluation process, 9% of the issues were

resolved by users without facilitator intervention.

Conclusion:

Among the identified usability challenges, layout and comprehensiveness were

reported as the most significant barriers affecting user experience.

Addressing these issues is crucial for enhancing the overall usability,

accessibility, and effectiveness of the Doctor Saina application.

|

|

Article

History:

Received: 2025-04-22

Accepted: 2025-05-10

Published: 2025-05-14

|

|

* Corresponding

author:

Mohammad Reza Mazaheri Habibi

Department of Health Information Technology,

Varastegan Institute for Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

Email:Mazaherim@Varastegan.ac.ir

|

|

Keywords:

Usability Evaluation

Mobile Health Applications

Doctor Saina

Telemedicine

Think-Aloud Method

|

|

Cite this paper as:

Raje F, Moghbeli F, Sangsefidi

Z, Maktabdar Roshkhar H, Mazaheri Habibi MR. Usability evaluation of the

Doctor Saina online consultation application using the think-aloud method. Adv

Med Inform. 2025; 1: 5.

|

Introduction

With the advancement of socioeconomic conditions and the

development of science and technology, healthcare and medical treatment have

significantly improved. However, due to disparities in economic development

between regions and urban-rural areas, the distribution of medical resources

has been skewed toward economically developed regions [1–3].

This unequal distribution of medical resources has led to

inadequate medical conditions and a decline in the quality and efficiency of

healthcare services in various areas. Consequently, access to medical care

remains a significant challenge for many people. Addressing the issue of

medical resource allocation and ensuring the effective sharing of these

resources is crucial for improving healthcare services and enhancing the

quality of medical care, particularly in underserved regions [4].

Telemedicine has been defined by the World Health

Organization (WHO) as “the delivery of healthcare services by healthcare

professionals using information and communication technologies.” This

technology facilitates the remote exchange of reliable information for

diagnosis, treatment, and disease prevention [5].

The emergence of telemedicine, which leverages

telecommunication technologies to deliver and support remote healthcare, has

ushered in a new era in healthcare provision. It offers numerous opportunities

for improving patient outcomes and expanding access to medical care. Its

applications include real-time video consultations, remote monitoring, and

mobile health applications, all designed to bridge the gap between patients and

healthcare providers. Telemedicine’s potential for enhancing patient outcomes

and healthcare access is multifaceted, addressing longstanding challenges such

as geographical barriers, provider shortages, and the need for timely medical

interventions. Additionally, it eliminates the necessity for long-distance

travel for patients in rural or underserved areas, reducing both the time and

costs associated with accessing healthcare. Furthermore, it provides a platform

for continuous monitoring and follow-up care, which is essential for managing

chronic diseases and improving overall health outcomes. The convenience and

flexibility of telemedicine also contribute to increased patient engagement and

adherence to treatment plans [6].

Telemedicine-based solutions are among the most effective

approaches for improving patient care quality and promoting self-management in patients

[7, 8]. According to the WHO,

“self-care” is defined as the ability of individuals, families, and communities

to promote health, prevent disease, maintain well-being, and cope with illness

and disability, with or without the support of a healthcare provider [9]. Access to technologies such as telemedicine enables

patients to take a more active role in their health-related activities, thereby

increasing their opportunities for self-care [10, 11].

In this regard, the widespread adoption of mobile

technology is being leveraged to enhance healthcare delivery. A broad range of

health applications has been introduced for monitoring, planning, and achieving

health-related goals. Given these advancements, smartphones have gradually

become an integral part of daily life, offering immense value in routine tasks.

Today, compared to the past, smartphones provide a wider array of functions and

features [12].

With the widespread use of smartphones and the expansion

of telemedicine, accessing medical services has become significantly easier.

Individuals can now conveniently obtain medical appointments, receive online

consultations, and manage their electronic health records [13].

As self-care and telemedicine gain traction among

patients, the number of e-health applications has increased exponentially in

recent years [14]. However, there is a growing body of

reports indicating that various usability deficiencies in these applications,

as well as in the environments where they are deployed, may ultimately affect

the quality of patient care [15].

Among the various factors

contributing to the abandonment or failure of an application, poor usability

remains one of the most critical barriers to its widespread adoption [16-18].

Usability refers to the ease with which users can learn,

interact with, and efficiently use a system, encompassing factors such as

learnability, efficiency, memorability, error prevention, and user

satisfaction. Therefore, evaluating the usability of health information systems

is essential for ensuring their effectiveness and user adoption [19-23].

A crucial component of self-care is the ability of

individuals to actively participate in their health management through healthy

lifestyle choices [24]. Studies suggest that 60% of

diseases can be prevented through effective self-care [25].

Chronic diseases pose a significant challenge to

healthcare systems, and self-care behaviors play a crucial role in managing and

treating chronic conditions [26]. Research has shown that

when patients have access to health technologies that empower them to take an

active role in their healthcare, their engagement in self-care significantly

improves [27].

Over the past few centuries, the sharing of medical

knowledge and telemedicine have evolved through technological advancements,

including the printing press, telegraph, telephone, and the internet [28].

Today, mobile technologies are more accessible than ever

and have been widely adopted in both the public and private sectors. One of the

most promising applications of mobile technology is its role in health

monitoring and management. Mobile health (mHealth) refers to any health-related

service that utilizes mobile devices, including phones, tablets, and wireless

technologies [29].

Through mobile health technologies, patients can monitor

their treatments, manage health-related concerns, and receive timely medical

assistance. These technologies are rapidly evolving, transforming how

healthcare services are delivered and accessed worldwide [30-32].

While smartphone applications have the potential to

enhance healthcare quality and accessibility, studies have identified usability

challenges that hinder effective user interaction with these applications.

Issues such as poor user-centered design, privacy concerns, and lack of

reliability in emergency situations have been cited as barriers to adoption [33].

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

defines usability as “the extent to which a product can be used by specified

users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency, and

satisfaction in a specified context of use” [14].

As usability becomes a critical factor in the adoption of

digital health applications, ensuring that these technologies are well-designed

and tailored to the needs of end-users is essential. This requires robust

usability evaluation methodologies to guarantee a seamless user experience.

Conducting usability assessments for digital health

applications offers substantial benefits, including enhanced efficiency,

improved user well-being, reduced stress, increased accessibility, and a lower

risk of user errors [34].

Usability evaluations help identify and address design

flaws that may negatively impact user interaction with web applications and

digital health platforms [35]. A well-designed health

information system with high usability can significantly improve healthcare

delivery, reduce errors, increase efficiency, and enhance user satisfaction [36]. Previous studies have demonstrated that usability

issues—such as unclear system messages and inefficient workflows—can reduce

user efficiency and hinder successful system interactions [37].

Various usability evaluation methods exist, depending on

factors such as the design phase, system complexity, target users, budget, and

time constraints [38, 39].

Material and Methods

Participants

The participants in this study were categorized into

three groups: users, facilitators, and technical support staff. The user group

consisted of 15 health information technology students from Varastegan

Institute for Medical Sciences. These individuals possessed knowledge of mobile

health application design, analysis, and user interface principles, but had no

prior experience with the Doctor Saina application. These users could

potentially serve as future system users. This study was conducted in

compliance with the ethical standards outlined in the Helsinki Declaration.

Before the evaluation commenced, participants were briefed on the study’s

objectives and general framework. Written and verbal informed consent was

obtained from all participants. Furthermore, their personal information was

handled confidentially, ensuring anonymity. Each user was accompanied by

a facilitator, who did not interfere with the evaluation process. Facilitators

only intervened if users encountered difficulties during usability testing,

reminding them to verbalize their thoughts. These facilitators were health

information technology specialists with experience in usability assessment. To

address potential technical issues during the evaluation, a software specialist

was also present as technical support.

Evaluation Tool

The evaluation was conducted in a quiet environment with

adequate lighting, a table, two chairs, and an Android smartphone with internet

access. Various tools were utilized to record user interactions, including:

•

Vidma REC (ver 2.6.14) to capture user interactions

with the application and verbal feedback.

•

A microphone and a video camera to record

participants’ voices and facial expressions.

A 15-part scenario comprising 10 usability tasks was

developed based on the application’s features (Appendix 1).

These tasks included:

1. User registration and profile editing

2. Accessing online medical consultations

3. Diagnosing conditions using the symptom checker

4. Assessing health status through the health checker

5. Reviewing the app’s health magazine

6. Exploring the at-home laboratory services

7. Accessing mental health services

8. Interacting with the health bank section

A widely accepted usability evaluation approach involves

real-user testing. In this study, the Think-Aloud method was employed, which is

an empirical approach focusing on observing users as they interact with the

system in real-time. This method gathers cognitive interaction data by

requiring participants to verbalize their observations, thoughts, emotions, and

decision-making processes while using the system.

Before the evaluation began, users received a 10-minute

training session on the Think-Aloud method, where they were instructed on how

to articulate their thoughts, emotions, and decisions in detail. After

completing the evaluation, participants were asked to provide suggestions for

improving the Doctor Saina application, which were documented in a structured

report form.

Analysis of Results

Following the completion of the assessments, the

researcher analyzed the recorded interactions, including Vidma REC files, audio

recordings, and user feedback reports. An independent review was conducted to

compile a comprehensive list of usability issues, along with their severity

levels.

Any discrepancies among researchers were resolved by

reviewing the recorded data.

For categorizing usability issues, the classification

method proposed by Van den Haak et al. was employed. According to this

approach, issues were grouped into four main categories:

•

Layout-related issues

•

Terminology-related issues

•

Data entry issues

•

Comprehensiveness issues

Apart from these four categories, users occasionally

encountered technological constraints, such as network connectivity problems.

Since these were not usability-related issues, they were excluded from the

analysis.

To assess the severity of usability problems, Nielsen’s

Heuristic Evaluation method was applied.

The Nielsen Questionnaire, developed by Jakob Nielsen,

includes ten fundamental principles for evaluating application usability:

1. System status visibility (awareness of navigation and

transitions);

2. Match between the system and the real world (use of familiar

terminology);

3. User control and freedom (easy navigation and exit options);

4. Consistency and adherence to standards;

5. Error prevention (minimization of incorrect data entry);

6. Recognition rather than recall;

7. Flexibility and efficiency of use;

8. Help users recognize, diagnose, and recover from errors;

9. Aesthetic and minimalist design;

10. Help

and documentation.

Using this heuristic framework, usability issues were

identified, and their potential impact on the user experience was assessed.

This method is widely recognized as an effective and cost-efficient approach

for evaluating clinical information systems and is extensively utilized in

usability assessments of user interfaces. According to Nielsen’s

classification, the severity of usability issues was categorized into five

levels (Table 1). However, issues ranked with a severity level of “0” were

excluded from the final list based on consensus among the researchers. Data

analysis was performed using SPSS (ver 26).

Table 1: Severity classification of usability

problems

|

Description

|

Severity

|

|

No usability problem

|

0

|

|

Cosmetic problem

|

1

|

|

Minor usability problem

|

2

|

|

Major usability problem

|

3

|

|

Usability catastrophe

|

4

|

Results

The user group in this study consisted of 15

participants, including 3 males (20%) and 12 females (80%), with an average age

of 20 years. The mean duration of the evaluation process for users was 22.08

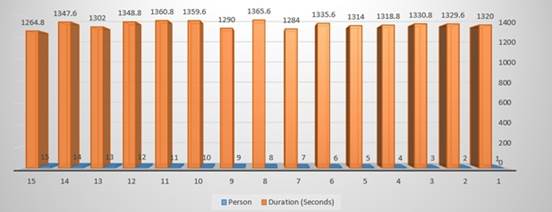

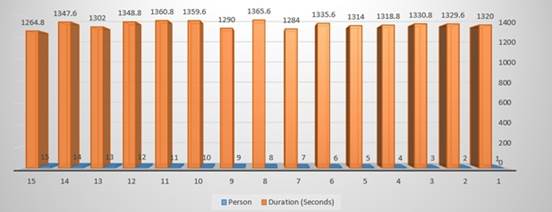

minutes. The evaluation time for each user is illustrated in Fig 1.

Fig 1: The evaluation time for each user

A total of 23 usability issues were identified by users

during the evaluation process. The categorization and severity levels of these

issues are presented in Table 2.

Among the identified issues, those related to

comprehensiveness were the most frequent, accounting for 10 cases (43.5%). As

shown in Table 2, approximately 40% of the issues in this category were

classified as minor (severity level 2).

The most frequently reported issue in this category was

the inability to enter miscellaneous symptoms in the disease diagnosis section

(Task 4), which was highlighted by 10 users. This was followed by the lack of

coordination for consultation regarding laboratory tests (Task 8), reported by

9 users.

As indicated in Table 2, layout-related issues accounted

for 4 cases (30.4%). Among these, 2 issues were rated as severity level 4. The

most frequently reported problems in this category were the absence of a

confirmation message after data entry (Task 3), reported by 10 users, and the

lack of proper categorization for physicians, reported by 8 users.

Table 2: Classification and Severity of

Usability Issues Identified by Users

|

Comprehensiveness

N (%)

|

Data entry

N (%)

|

Terminology

N (%)

|

Layout

N (%)

|

Variables

|

|

10(43.5)

|

3(13.0)

|

3(13.0)

|

7(30.4)

|

Usability Problem

|

|

5(50.0)

|

2(66.7)

|

2(66.7)

|

4(57.1)

|

1

|

Severity

|

|

4(40.0)

|

0

|

0

|

1(14.3)

|

2

|

|

1(10.0)

|

1(33.3)

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

|

0

|

0

|

1(33.3)

|

2(28.6)

|

4

|

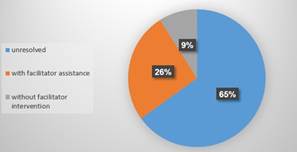

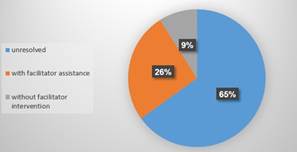

Fig 2 illustrates how usability issues were addressed by

users during the evaluation process.

According to this figure:

•

2 issues (9%) were resolved by users independently,

without facilitator intervention.

•

6 issues (26.0%) were resolved with facilitator

assistance, without interrupting the evaluation process.

•

15 issues (65.2%) remained unresolved after user

attempts and were bypassed, allowing the evaluation process to continue without

completing the associated tasks.

A summary of all identified issues by users and

specialists is presented in Table 3.

Fig 2: Illustrates how usability issues were

addressed by users during the evaluation process

During the 15 evaluations using the think-aloud method,

23 issues were identified, none of the users utilized the system’s help

feature. Additionally, 8 users provided suggestions for improving the system’s

performance. The most common suggestions were related to improving the design

of the doctor classification section and enhancing the notifications for

operations within the application’s service sections.

discussion

Usability studies of the Doctor Saina application in the

healthcare domain require serious attention. Usability is a crucial part of

developing this application, especially when the goal is to improve the

physical health of the patient. In this study, the usability of the Doctor

Saina application was evaluated using the think-aloud method. During the

evaluation process, 23 issues were identified by the users, 5 of which had a

severity greater than 2. While the participants generally assessed the

usability of the application as good, some issues remained that could be

addressed to improve the user experience. The most frequent usability issues

identified by users were in the Comprehensiveness category (43.5%). The two

most common issues were: the inability to record symptoms other than those

listed in the disease diagnosis section and the lack of a time frame for

scheduling phone consultations after a test request was made. These issues may

have arisen due to the limited options available in the symptom list, which may

not be comprehensive or aligned with user needs, and the lack of clarity in

scheduling physician availability.

During the evaluation process, 9% of the issues were

resolved by users without facilitator intervention. Additionally, 65% of the

issues remained unresolved, and 26% of the remaining issues were resolved with

the facilitator’s help.

Table 3: Identified Usability Issues

|

Issues

|

Users

|

|

Layout

|

1- The diagnostic tool lacks a

symptom search feature. (5 users / Severity: 4)

2- The psychological assessment

section does not include a back-navigation option. (6 users / Severity: 1)

3- Healthcare facility locations

are not integrated with navigation applications. (3 users / Severity: 1)

4- After completing registration

and updating their profile, users do not receive a confirmation message

(e.g., “Registration Successful”). (10 users / Severity: 1)

5- The specialty selection menu

for choosing a physician for medical consultation would be more user-friendly

if presented as a dropdown menu. (8 users / Severity: 4)

6- The active/inactive status of

physicians is not clearly visible to users. (3 users / Severity: 2)

7- The health database and

medical journal sections primarily contain text-based information, lacking

engaging graphical content. (3 users / Severity: 1)

|

|

Data entry

|

1- When applying filters to find

physicians, the results do not accurately reflect the selected filters. (7

users / Severity: 3)

2- Comments and reviews are not

restricted to patients who have had a consultation—any user, even without a

prior visit, can submit a review. (1 user / Severity: 1)

3- The validation process for

user profile data is not sufficiently robust. (2 users / Severity: 1)

|

|

Terminology

|

1- Instead of displaying an error

message when accessing the herbal medicine section, the system should provide

a message indicating the activation date. (15 users / Severity: 4)

2- The meaning of an “active” or

“inactive” physician was unclear to users. (4 users / Severity: 1)

3- The medical conditions

section within the health database is overly technical and not suitable for

general users. (2 users / Severity: 1)

|

|

Comprehensiveness

|

1-The physician recommendation

system is solely based on response time and frequency, without considering

physician experience or patient satisfaction. (1 user / Severity: 1)

2-The diagnostic tool lacks high

accuracy in identifying diseases. (8 users / Severity: 3)

3-Users cannot input symptoms

that are not already listed in the diagnostic section. (12 users / Severity:

1)

4-The recommended physician at

the end of the diagnosis process does not necessarily match the probable

diagnosis. (6 users / Severity: 2)

5-The search and filter

functions in the health database allow searches only by location, not by

medical specialty or condition. (3 users / Severity: 1)

6-Information regarding

healthcare service centers within the health database is not fully accurate.

(1 user / Severity: 1)

7-The reliability of

psychological assessments and their sources is not clearly stated. (2 users /

Severity: 2)

8-The application does not

include a section for submitting and tracking laboratory test requests. (1

user / Severity: 1)

9-No time frame is provided for

scheduling a follow-up call after requesting an at-home lab test. (9 users /

Severity: 2)

10-The integration of medical

consultation payments with insurance is problematic due to limited agreements

with different insurance providers. (7 users / Severity: 2)

|

The goal of usability testing is to identify usability

problems in the system and provide solutions for addressing these issues. In

this context, users made several suggestions to improve the system’s

performance. Most of these suggestions focused on improving the design and

categorization of certain fields, such as creating a more user-friendly

classification of doctors in the online medical consultation section.

One critical aspect that requires further review and

attention is for users who may face equipment limitations. It is recommended

that telephone-based support be provided for these users. Another consideration

is for users with visual, auditory, or physical impairments, for whom the

application’s features do not currently provide solutions. In the future,

solutions such as voice guidance, vibration, or non-verbal solutions could help

address these limitations.

One limitation of this study was that the evaluation

sessions were conducted in a laboratory setting. Users might interact with the

application more comfortably in a real-world environment, possibly having

different opinions on the issues and their severity. On the other hand, one of

the key strengths of this study was the precise think-aloud usability test of

the Doctor Saina online medical consultation application. Moreover, this study

is one of the few conducted in this area in Iran.

Question 1: What is the severity of issues related to

receiving online medical consultations in video, phone, and text formats?

This service is accessible in the “My Health” section of

the Doctor Saina application under the medical consultation section. The most

frequent usability issues encountered by users in online medical consultations

were in the Layout category. Two of the most common issues were related to the

categorization of doctors in the initial online medical consultation section.

It might be more effective to align the doctor categorization with the system

used for selecting treatment centers in the Health Bank section to allow for

easier specialization-based doctor selection.

Question 2: What is the severity of issues related to

receiving online laboratory services?

Access to this service is available in the “Tests at

Home” section of the Doctor Saina application. The most significant issue in

this section was related to Comprehensiveness. The user reported that after

submitting a test request, there was no time frame provided for coordination.

The application only stated that the user would be contacted “as soon as

possible,” but the user was not informed about the time range for the call.

Another issue was related to the inability of the user to use their supplemental

insurance due to the lack of an agreement between the application and the

user’s insurance company. This issue arose from the limitations in contracts

with different insurance companies. Since users prefer to use their

supplementary insurance over the free-market prices, this is a significant

factor.

Question 3: What is the severity of issues related to

receiving health and disease diagnosis services online?

Access to this service is available through the “My

Health” section of the Doctor Saina application. The most significant usability

issues in the health and disease diagnosis section were also in the

Comprehensiveness category. The first issue was related to the search and

selection of disease symptoms, where users could not find their symptoms in the

available list. Another issue was the inaccuracy of disease diagnosis based on

the symptoms entered by the users. Lastly, there was a mismatch between the doctor

and the disease according to the symptoms entered. This may have been caused by

inadequate categorization of the symptom, diagnosis, and specialty information.

Question 4: What is the severity of issues related to

receiving general information from the Health Magazine?

This section of the application is accessible through the

Health Magazine section. This section had the fewest issues for users, with the

only complaint being related to the lack of visual appeal and graphics, which

is a Layout issue.

Question 5: What is the severity of usability issues in

the Doctor Saina web application?

Users reported several significant issues with the Doctor

Saina application. One issue was the limitation of the symptom list in the

disease diagnosis section, which prevented users from entering symptoms outside

the predefined list. Additionally, most users experienced issues with not

receiving confirmation after editing and saving their profile information,

which was ranked with a severity of 1. Other common issues included the

inability to cooperate with different insurance companies and inaccuracies in

disease diagnosis, which were ranked with a severity of 2. The most frequent

issue related to the lack of access and awareness of the time for resuming

access to the pharmacy and herbal medicine sections of the Health Bank, as well

as the lack of proper categorization of specialties in the online medical consultation

section, both of which were identified as critical issues with a severity of 4.

If, after this study, the application management and

support team address these issues, it can enhance the accuracy of disease

diagnosis for users. Furthermore, if the application collaborates with various

insurance companies, users would no longer have to chase insurance claims after

consultations. Additionally, reducing the time users spend navigating the

application would lead to a more efficient and user-friendly experience.

Conclusion

The user evaluation of the Doctor Saina application

revealed that despite being a new application designed with attention to user

needs and established standards, several usability issues remain. The most

frequent issues were identified in the Comprehensiveness category. If these

problems are not addressed, they may negatively impact user performance,

leading to fatigue, confusion, wasted time, and, ultimately, user

dissatisfaction. This dissatisfaction could escalate into errors, reduced

treatment quality, and potentially jeopardize patient health.

The findings underscore the importance of adhering to

established human-computer interaction standards to prevent such issues.

Addressing the 23 identified usability issues and making the necessary

improvements will enhance the overall user experience. The management team of

the Doctor Saina web application has been notified of these issues, with

recommendations for improvement to ensure a more efficient and user-friendly

system.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by Varastegan Institute for

Medical Sciences. We thank all participants for the collaboration in this

study.

Author’s contribution

FR:

Data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafting the work; FM:

Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafting the work; ZS:

Drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content; HMR:

Drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content; MRMH:

Design of the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content.

All authors contributed to the literature review, design,

data collection, drafting the manuscript, read and approved the final

manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding

the publication of this study.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the ethical committee of

Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (approval number IR.MUMS.REC.1402.034).

Financial disclosure

No financial interests related to the material of this

manuscript have been declared.

References

1.

Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J

Med. 2016; 375(2): 154-61. PMID: 27410924 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1601705

[PubMed]

2.

Parikh D, Armstrong G, Liou V, Husain D. Advances

in telemedicine in ophthalmology. Semin Ophthalmol. 2020; 35(4): 210-5. PMID: 32644878 DOI: 10.1080/08820538.2020.1789675 [PubMed]

3.

Hadziahmetovic M, Nicholas P, Jindal S, Mettu PS,

Cousins SW. Evaluation of a remote diagnosis imaging model vs dilated eye

examination in referable macular degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019; 137(7): 802-8.

PMID: 31095245 DOI: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.1203 [PubMed]

4.

Su Z, Li C, Fu H, Wang L, Wu M, Feng X. Development

and prospect of telemedicine. Intelligent Medicine. 2024; 4(1): 1-9.

5.

Naik N, Ibrahim S, Sircar S, Patil V, Hameed BM,

Rai BP, et al. Attitudes and perceptions of outpatients towards adoption of

telemedicine in healthcare during COVID-19 pandemic. Ir J Med Sci. 2022; 191(4):

1505-12. PMID: 34402031 DOI: 10.1007/s11845-021-02729-6

[PubMed]

6.

Ezeamii VC, Okobi OE, Wambai-Sani H, Perera GS,

Zaynieva S, Okonkwo CC, et al. Revolutionizing healthcare: How telemedicine is

improving patient outcomes and expanding access to care. Cureus. 2024; 16(7): e63881.

PMID: 39099901 DOI: 10.7759/cureus.63881 [PubMed]

7.

Gholamzadeh M, Abtahi H, Safdari R. Telemedicine in

lung transplant to improve patient-centered care: A systematic review. Int J

Med Inform. 2022; 167: 104861. PMID: 36067628 DOI: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2022.104861

[PubMed]

8.

Aalaei S, Amini M, Mazaheri Habibi MR, Shahraki H,

Eslami S. A telemonitoring system to support CPAP therapy in patients with

obstructive sleep apnea: A participatory approach in analysis, design, and

evaluation. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2022; 22(1): 168. PMID:

35754055 DOI: 10.1186/s12911-022-01912-8

[PubMed]

9.

World Health Organization. Diabetes [Internet].

2024 [cited: 25 Sep 2024]. Available from: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes

10.

Agarwal E, Miller M, Yaxley A, Isenring E.

Malnutrition in the elderly: A narrative review. Maturitas. 2013; 76(4): 296-302.

PMID: 23958435 DOI: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.07.013 [PubMed]

11.

Agha Seyyed Esmaeil Amiri FS, Bohlouly F,

Khoshkangin A, Razmi N, Ghaddaripouri K, Mazaheri Habibi MR. The effect of

telemedicine and social media on cancer patients' self-care: A systematic

review. Frontiers in Health Informatics. 2021; 10: 92.

12.

Mubeen M, Iqbal MW, Junaid M, Sajjad MH, Naqvi MR,

Khan BA, et al. Usability evaluation of pandemic health care mobile

applications. IOP conference series: Earth and environmental science; 2021.

13.

Al-Marsy A, Chaudhary P, Rodger JA. A model for

examining challenges and opportunities in use of cloud computing for health

information systems. Applied System Innovation. 2021; 4(1): 15.

14.

Maramba I, Chatterjee A, Newman C. Methods of

usability testing in the development of eHealth applications: A scoping review.

Int J Med Inform. 2019; 126: 95-104. PMID: 31029270 DOI: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.03.018

[PubMed]

15.

Watbled L, Marcilly R, Guerlinger S, Bastien JM,

Beuscart-Zéphir MC, Beuscart R. Combining usability evaluations to highlight

the chain that leads from usability flaws to usage problems and then negative

outcomes. J Biomed Inform. 2018; 78: 12-23. PMID: 29305953 DOI: 10.1016/j.jbi.2017.12.014

[PubMed]

16.

Khajouei R, Hasman A, Jaspers MW. Determination of

the effectiveness of two methods for usability evaluation using a CPOE

medication ordering system. Int J Med Inform. 2011; 80(5): 341-50. PMID: 21435943 DOI: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.02.005 [PubMed]

17.

Campbell EM, Guappone KP, Sittig DF, Dykstra RH,

Ash JS. Computerized provider order entry adoption: Implications for clinical

workflow. J Gen Intern Med. 2009; 24(1): 21-6. PMID: 19020942 DOI: 10.1007/s11606-008-0857-9

[PubMed]

18.

Kim MS, Shapiro JS, Genes N, Aguilar MV, Mohrer D,

Baumlin K, et al. A pilot study on usability analysis of emergency department

information system by nurses. Appl Clin Inform. 2012; 3(1): 135-53. PMID: 23616905 DOI: 10.4338/ACI-2011-11-RA-0065 [PubMed]

19.

Khajouei R, Azizi AA, Atashi A. Usability

evaluation of an emergency information system: A heuristic evaluation. Journal

of Health Administration. 2013; 16(52): 61-72.

20.

Nielsen J. Usability engineering. Academic Press;

1993.

21.

Mazaheri Habibi MR, Khajouei R, Eslami S, Jangi M,

Ghalibaf AK, Zangouei S. Usability testing of bed information management

system: A think-aloud method. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2018; 9(4): 153-7. PMID: 30637234 DOI: 10.4103/japtr.JAPTR_320_18 [PubMed]

22.

Ghalibaf AK, Jangi M, Mazaheri Habibi MR, Zangouei

S, Khajouei R. Usability evaluation of obstetrics and gynecology information

system using cognitive walkthrough method. Electron Physician. 2018; 10(4): 6682-8.

PMID: 29881531 DOI: 10.19082/6682 [PubMed]

23.

Jangi M, Khajouei R, Tara M, Mazaheri Habibi MR,

Ghalibaf AK, Zangouei S, et al. User testing of an admission, discharge,

transfer system: Usability evaluation. Frontiers in Health Informatics. 2021; 10:

77.

24.

Narasimhan M, Kapila M. Implications of self-care

for health service provision. Bull World Health Organ. 2019; 97(2): 76-A. PMID: 30728611 DOI: 10.2471/BLT.18.228890 [PubMed]

25.

Zhang X, Foo S, Majid S, Chang Y-K, Dumaual HTJ,

Suri VR. Self-care and health-information-seeking behaviours of diabetic

patients in Singapore. Health Commun. 2020; 35(8): 994-1003. PMID: 31303050 DOI: 10.1080/10410236.2019.1606134 [PubMed]

26.

Koirala B, Himmelfarb CRD, Budhathoki C, Davidson

PM. Heart failure self-care, factors influencing self-care and the relationship

with health-related quality of life: A cross-sectional observational study. Heliyon.

2020; 6(2): e03412. PMID: 32149197 DOI: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03412 [PubMed]

27.

Jin MX, Kim SY, Miller LJ, Behari G, Correa R.

Telemedicine: Current impact on the future. Cureus. 2020; 12(8): e9891. PMID: 32968557 DOI: 10.7759/cureus.9891 [PubMed]

28.

Seppälä J, De Vita I, Jämsä T, Miettunen J,

Isohanni M, Rubinstein K, et al. Mobile phone and wearable sensor-based mHealth

approaches for psychiatric disorders and symptoms: Systematic review. JMIR Ment

Health. 2019; 6(2): e9819. PMID: 30785404 DOI: 10.2196/mental.9819

[PubMed]

29.

Tas B, Lawn W, Traykova EV, Evans RA, Murvai B,

Walker H, et al. A scoping review of mHealth technologies for opioid overdose

prevention, detection and response. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2023; 42(4): 748-64. PMID: 36933892 DOI: 10.1111/dar.13645 [PubMed]

30.

Torous J, Nicholas J, Larsen ME, Firth J,

Christensen H. Clinical review of user engagement with mental health smartphone

apps: Evidence, theory and improvements. Evid Based Ment Health. 2018; 21(3): 116-9.

PMID: 29871870 DOI: 10.1136/eb-2018-102891 [PubMed]

31.

Moghbeli F, Setoodefar M, Mazaheri Habibi MR,

Abbaszadeh Z, Keikhay Moghadam H, Salari S, et al. Using mobile health in

primiparous women: Effect on awareness, attitude and choice of delivery type,

semi-experimental. Reprod Health. 2024; 21(1): 49. PMID: 38594731 DOI: 10.1186/s12978-024-01785-2

[PubMed]

32.

Khoshkangin A, Agha Seyyed Esmaeil Amiri FS,

Ghaddaripouri K, Noroozi N, Mazaheri Habibi MR. Investigating the role of

mobile health in epilepsy management: A systematic review. J Educ Health

Promot. 2023; 12: 304. PMID: 38023071 DOI: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_1188_22

[PubMed]

33.

Agapito G, Cannataro M. An overview on the challenges

and limitations using cloud computing in healthcare corporations. Big Data and

Cognitive Computing. 2023; 7(2): 68.

34.

Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Papoutsi C, Lynch J,

Hughes G, Hinder S, et al. Beyond adoption: A new framework for theorizing and

evaluating nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread,

and sustainability of health and care technologies. J Med Internet Res. 2017; 19(11):

e367. PMID: 29092808 DOI: 10.2196/jmir.8775 [PubMed]

35.

Lawal FB, Omara M. Applicability of dental patient

reported outcomes in low resource settings–a call to bridge the gap in clinical

and community dentistry. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2023; 23(1S): 101789. PMID: 36707169 DOI: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2022.101789 [PubMed]

36.

Oliveira Chaves L, Gomes Domingos AL, Louzada

Fernandes D, Ribeiro Cerqueira F, Siqueira-Batista R, Bressan J. Applicability

of machine learning techniques in food intake assessment: A systematic review. Crit

Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2023; 63(7): 902-19. PMID: 34323627 DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2021.1956425

[PubMed]

37.

Damiani M, Sinkko T, Caldeira C, Tosches D,

Robuchon M, Sala S. Critical review of methods and models for biodiversity

impact assessment and their applicability in the LCA context. Environmental

Impact Assessment Review. 2023; 101: 107134.

38.

Thyvalikakath TP, Monaco V, Thambuganipalle H,

Schleyer T. Comparative study of heuristic evaluation and usability testing

methods. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2009; 143: 322-7. PMID: 19380955 [PubMed]

39.

Yen PY, Bakken S. A comparison of usability

evaluation methods: Heuristic evaluation versus end-user think-aloud protocol –

An example from a web-based communication tool for nurse scheduling. AMIA Annu

Symp Proc. 2009; 2009: 714-8. PMID: 20351946 [PubMed]

Appendices

Appendix 1

1. Usability Evaluation Scenario of the Doctor Saina Application

2. In the first task, the user must open the application and

register as a user by providing their personal information.

3. In the second task, the user accesses their profile section and

completes or edits their personal information.

4. Additionally, in the profile section, the user encounters

several items related to their user profile, which we asked them to review.

These items include: My Conversations, My Doctors, My Appointments, Favorites,

Financial Transactions, Support Requests, Frequently Asked Questions, Referral

to Friends, and Rating Doctor Saina.

5. In the third task, the user proceeds to the “My Health” section

to initiate an online medical consultation.

6. In this section, based on the user’s selection of a specialty or

doctor, they can choose to receive a consultation either by phone, urgent phone

call, text, or video, according to various criteria such as user reviews, the

doctor’s medical background, and successful consultations.

7. If the selected doctor is available, the user proceeds with the

consultation by choosing their primary and supplementary insurance and making

the payment.

8. If the doctor is unavailable, the user can either select an

alternative doctor or be notified when their chosen doctor becomes available.

9. In the fourth task, the user must use the “Disease

Diagnostician” section within the “My Health” section to begin the diagnostic

process for a potential illness based on their symptoms.

10. After

completing the diagnostic steps, the possible diagnosis is presented, and the

user can schedule a consultation with a doctor for further confirmation if

necessary.

11. In

the fifth task, the user is required to complete information in the “My Health”

section to receive a body health analysis.

12. In

the sixth task, the user must check useful and categorized health-related

articles in the “Health Magazines” section of Doctor Saina’s services.

13. In

the seventh task, the user can view their medical consultation history in the

“Conversations” section, categorized as: All, Pending Payment, and Completed.

14. In

the eighth task, the user can request an in-home laboratory test service

through the “Home Testing” section, and receive an interpretation of their test

results with the assistance of doctors.

15. In

the ninth task, the user can take a psychological test and receive analysis and

counseling in the “Psychological Testing” section.

16. In

the tenth task, the user can utilize the “Health Bank” section to access

information on medical centers, health services across the country, as well as

information on medications, herbal drugs, and diseases.